New partnership to quickly detect water supply and demand changes

Think of Arizona’s biggest water issues and three immediately come to mind: the Colorado River, high country snowpack and groundwater. Although each topic presents its own unique set of challenges, improving measurement and monitoring in these critical arenas can help managers to quickly and accurately respond to changes in water supply and demand.

A new partnership between Planet, a satellite imaging company, and the Arizona Water Innovation Initiative (AWII), a multi-year partnership with the state led by Arizona State University’s Julie Ann Wrigley Global Futures Laboratory in collaboration with the Ira A. Fulton Schools of Engineering, is supporting researchers in assessing and monitoring water supply and demand at higher resolution in both time and space than ever before.

Enrique Vivoni, director of the Center for Hydrologic Innovations and Fulton Professor of Hydrosystems Engineering, explains that the resolution of Planet’s satellite-based products is a game changer.

“The near daily, and sometimes even more frequent, high resolution imagery from Planet’s constellation of satellites assists us in monitoring changes on the land surface. This includes measuring and monitoring snowpack and agricultural activity, which are important for understanding water supply and demand.”

The frequency of Planet’s imaging is particularly valuable because when it comes to water in an arid climate, things can change very quickly. For example, snow tends to melt quickly in the Arizona sun and therefore imaging that takes place every couple of weeks or months might miss important water supply and demand information.

The partnership with Planet allows ASU researchers to also develop new algorithms that can be used to inform decision-making by water agencies and managers.

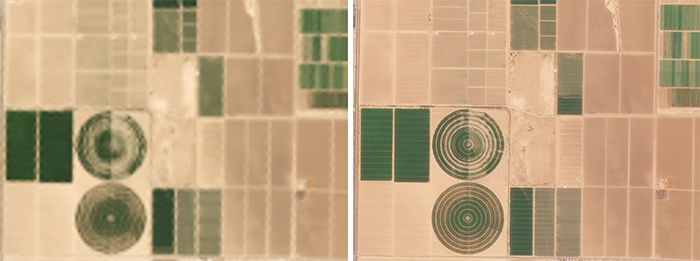

For example, long-term drought in the Colorado River Basin led to the declaration of water shortages that have in turn reduced water deliveries to the Central Arizona Project (CAP). Vivoni, who is also a pillar leader for AWII, and his team are conducting a retrospective study with high resolution Planet data that will provide a new view of how water policy triggers in the Basin impacted crop production and agribusiness in Arizona.

"Frequently captured, high-resolution images provide a unique and detailed understanding of the intricate, dynamic changes occurring across crops over time," says Shraddha Sharma, a graduate student researcher on the project.

Understanding how drought shortages impacted crop production is critical for agricultural production, water security and economic development.

“We’re curious what these policy changes did to farmers' decisions about the type of crop they farmed, how many acres they had that particular year and whether there is a differential response,” says Vivoni. “Some farmers have senior water rights and they likely did not suffer any water reductions, whereas farmers in other irrigation districts with more junior water rights had to either fallow fields or switch over to groundwater use, which meant refurbishing old wells or installing new wells.”

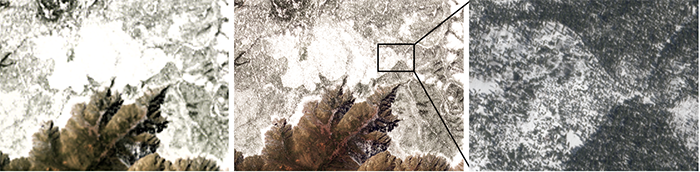

With supply reductions from the Colorado River system, the need for a reliable water supply from the Salt and Verde River watershed to support the Phoenix metropolitan area is paramount. The Salt River Project has a robust approach to managing this system that includes snowpack monitoring, streamflow forecasting and reservoir operations. However, management challenges remain due to variable snowpack dynamics.

“Over 80 percent of the streamflow from the Salt and Verde Rivers originates from snowmelt, making accurate snowpack mapping important for predicting water supply,” says Zhaocheng Wang, a postdoctoral scholar and principal investigator on the project. “The three-meter resolution data provided by Planet allows us to map the snowpack extent within the watershed, which can help the utility determine the snowpack level and predict streamflow volume. The high temporal resolution is also important, as it captures the fast cycle of snow accumulation and melting, which is often missed in commonly used LandSat images.”

“Such advancements will enhance water security in Arizona,” Vivoni adds. “We expect the platform to be useful for other agencies, utilities, communities, farmers and industries. In a broader context, the snow monitoring algorithm also has global applicability.”

Similarly, groundwater supplies are being tested not only in Arizona but around the world. In Arizona, groundwater makes up 40 percent of the state’s overall water supplies. However, measuring and monitoring this crucial resource can be particularly challenging because it is found beneath land surfaces, which is where satellite-based data comes in.

Jay Famiglietti, Global Futures Professor and science director for AWII, is using Planet’s soil moisture products – available in both one-kilometer and 100-meter resolutions – to enhance NASA's GRACE-based groundwater storage estimates, which are currently available at a 25-kilometer resolution.

“The high resolution soil moisture data will add important spatial information to the more coarse resolution GRACE data, so that we can produce one-kilometer maps of groundwater storage changes for all of Arizona,” says Famiglietti. “This is a process that will help us to get to the spatial and temporal scales at which water decisions are actually made, as well as improve our overall measurement and monitoring of the state’s crucial groundwater supplies.”

ASU was the first university to partner with Planet. Vivoni says that collaboration came about because of the university’s innovation focus, as well as the reach of the academic and research enterprises.

“As an early adopter of Planet data, I’ve seen how valuable it is in our classroom settings and for our research activities. A university is a great sandbox for testing algorithms. For example, some of the algorithms that were built for forestry applications were focused on tropical forests and might not work in the conifer forests that feed our water supply here in Arizona. Recently, we've started to interact with researchers at Planet and that's been very good for our long-term collaboration.”

Vivoni also emphasizes the importance of involving graduate students and post-doctoral researchers in the work.

“It's really important to me that graduate students and postdocs are acknowledged as the folks that are doing the work. The faculty are managing a project that's being done by these creative young minds.”

The researchers hope that the Planet partnership leads to products that are new and innovative that can then be adopted back by the company. Vivoni is particularly excited about creating dashboards – online visualization platforms – with this kind of high resolution data.

“Within AWII, we’re creating an online water observatory that aides decision makers so they can say ‘this is how our watersheds, groundwater systems and forested areas have been behaving in the last three months,’ and they have a better understanding of the context for the decisions that need to be made today.”

Vivoni says it is by design that he works with decision makers and managers at state agencies and utilities from the beginning of his projects; doing so leads to an end product that's most closely tied to their needs.

“It's very easy for technologists, engineers and scientists to take on a project and go away for two or three years and then come back and say, ‘look what I solved.’ And suddenly what was solved has no relevance to the initial question that was posed because there was no interaction along the way. We’re trying to break that mold by interacting early and often with the people who are using our research results.”

Related stories: