New methods for mapping and monitoring Arizona snowpack for water supply planning

Winters in the Arizona high country offer the best of both worlds: snowstorms that quickly give way to sunshine, often within a matter of hours or days. However, that same dynamic where snow is there one minute and gone the next makes measuring and monitoring the snowpack for water supply planning purposes challenging.

Researchers with the Arizona Water Innovation Initiative (AWII) – a multiyear program supported by the state and led by ASU’s Julie Ann Wrigley Global Futures Laboratory in collaboration with the Ira A. Fulton Schools of Engineering – are tackling this challenge with innovative new data and methods for analyzing snowpack in ways that are useful to water managers.

The project is led by Zhaocheng Wang, a postdoctoral scholar with AWII and the Center for Hydrologic Innovations (CHI), and was supported by a 2023 ASU and Planet seed grant. Wang was introduced to hydrology as an exchange undergraduate student at ASU and returned to pursue his graduate studies in watershed hydrology with Professor Enrique Vivoni, director of CHI and pillar lead with AWII.

Wang was drawn to working in this area in large part because of Vivoni's orientation toward collaborating directly with the end users of the products researchers are creating, ensuring that the work they do is beneficial.

“We go to water managers and ask them what kinds of information could make their jobs easier, and then we tackle that,” says Wang. “We're not just answering the research questions that interest us, we're really asking what water practitioners need and doing what we can to address those needs.”

In this case, Wang worked with the power and water utility Salt River Project (SRP) to develop a method to leverage existing snowpack monitoring methods – including snow stations and helicopter flights – in the Salt and Verde watersheds with high resolution imagery from Planet and advanced machine learning and artificial intelligence approaches.

Why measuring snow accurately matters

“Snow is a natural reservoir because, unlike rain, it doesn’t immediately infiltrate into the soil or flow to a stream channel,” says Wang. “It can instead be stored in high elevation areas, then melt and move more slowly into lakes and reservoirs for later use.”

That natural reservoir of snow is particularly important in the western US, where spring snowmelt is often used to get the region through drier and hotter times. However, Arizona’s snowpack is more ephemeral than much of the rest of the region. In addition, the state’s rugged terrain and vegetation strongly affect the snowpack on the ground, creating complex snow patterns.

“The system is incredibly dynamic, which makes it both interesting and challenging to study,” says Wang. “High resolution remote sensing and machine learning approaches offer a new way to monitor snow in areas where it transits quickly, as well as to more strategically complete ground observations.”

Much of Arizona’s precipitation – whether rain or snow – comes in “pulses”, notes Wang. During the monsoon season for example, rains can be quite heavy but intermittent. When it comes to snow, we might go from zero snow to 100% snow coverage and back again in a matter of days.

“It's important to capture snowpack in Arizona because much of what becomes our water supply develops in the winter time,” says Wang. “Water managers maintain reservoirs so that they can slowly release water throughout the year which is important for water security.”

Innovative methods for analyzing snowpack in the desert

Snow has been monitored and studied using remote sensing for decades. However, the predominant satellite imagery used is coarse in spatial scale – about 500 meters in resolution. Wang explains that the methods traditionally used with that data can lead to both under and overestimation of snowpack. That’s where using Planet’s three meter resolution data is a gamechanger.

“Planet imagery is useful for the type of dryland hydrology we have in Arizona,” says Wang. “We really need both the high resolution spatial and temporal data due to the quick melting of our snowpack.”

In addition to high resolution data, Wang and his team are innovating machine learning methods to get at previously difficult to measure variables like snow in shadows or under trees.

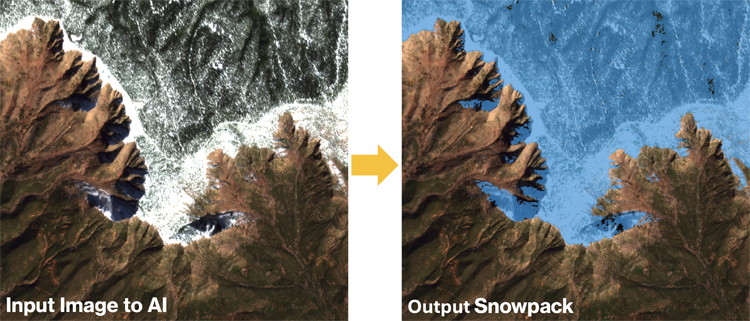

“We trained a machine learning model called a convolutional neural network that can get the snowpack in different spatial patterns by using the surrounding pixels for additional information for contextual information,” says Wang. “If you look at the three meter imagery, you can use your human eye to visually see if it's snow or no snow. So essentially we are training a machine learning model that mimics the human eye.”

Rather than reinventing AI tools, the team is focused on harnessing cutting-edge technologies and applying them to the field of hydrology. Working with three graduate students from computer science at ASU, Jaya Venkatesh, Shrey Malvi and Maneesh Sistla, Wang was able to explore cutting edge machine learning and artificial intelligence approaches, while applying his own domain expertise in hydrology.

“It’s been a great team effort. Dr. Vivoni is the co-lead on the project and we’re working directly with Bo Svoma, a climate scientist and meteorologist at SRP, along with the ASU computer science students,” explains Wang. “The students don’t know hydrology, but are experts at machine learning, and we know the hydrology. It's really a perfect combination where everyone brings their own expertise, and that makes innovation happen.”

Supporting water management decisions

“In dryland regions like Arizona, every drop counts,” says Wang.

For example, Arizona’s 2023 wet winter led to SRP releasing water from reservoirs earlier than they would have liked to make space for additional snowmelt. Having a better sense of exactly how much water they might expect could help to bolster water supplies by not releasing water from reservoirs unnecessarily.

“A substantial portion of the SRP water we use in the Phoenix Metro area comes from Arizona’s high elevation snowmelt that feeds into the reservoir system,” says Bo Svoma of SRP. “Accurately understanding how much snow is on the watershed is also important for forecasting the timing of streamflow into our reservoirs, which is crucial for better managing water supplies.”

The success of the pilot project led to further funding from the US Bureau of Reclamation to integrate LiDAR data and hydrologic modeling to create a new snowpack-to-streamflow measurement and modeling system for SRP watersheds in Arizona. Wang notes that there are many factors that contributed to that success.

“To do machine learning well, you have to have the infrastructure, and research computing at ASU provides these resources. You also need a workforce and ASU has a very strong computer science department that trains a lot of very talented machine learning engineers,” says Wang. “Finally, data is crucial to train any machine model, which we were able to obtain from SRP. If any of those pieces had been missing, we wouldn’t have been able to do the work.”

Because of this project, the team developed an open source, online visualization platform to see the snowpack. It's a prototype of how ASU researchers directly engage with end users to develop a product that is relevant for regional water management.

“These machine learning and AI techniques allow unprecedented views of the Earth’s land surface,” says Vivoni. “This is a great opportunity to apply AI methods to address water management challenges that were previously difficult to solve using traditional tools and methods.”

Related stories: