Northern Arizona gathering highlights diverse rural groundwater concerns

Northern Arizona’s high elevation mix of forests, mountains and plains leads to different water challenges than those that face the rest of the state. While recent research has shown that the southeastern and western parts of the state are facing severe groundwater declines, Northern Arizona is in less dire straits. However, that doesn’t mean residents aren’t concerned.

Ron Doba, coordinator for the Coconino Plateau Water Advisory Council and Watershed Partnership, was one of several water leaders across the state to reach out to Impact Water - Arizona, a program of the Arizona Water Innovation Initiative housed in the Julie Ann Wrigley Global Futures Laboratory at Arizona State University, in response to a call to co-develop rural groundwater resilience workshops.

“Anyone reading the news knows there are groundwater issues in Arizona,” said Doba. “Declining groundwater and land subsidence don’t feel like a threat here on the Coconino Plateau, but we want to be proactive to avoid the problems other parts of the state are facing.”

To identify challenges before they turn to crises, the community was most interested in making sure that they have the best information they can to plan for the future.

“What data do we have? Do we have enough? If not, how do we get it?” Doba asked as he opened the workshop. “Who will manage and analyze that data? And will we have the political will to protect groundwater to ensure long-term resilience on the Plateau? These are the questions we’re here to tackle.”

The hydrology of the Coconino Plateau

To begin to address those questions, Neha Gupta of the Arizona Institute for Resilience at the University of Arizona, a key partner in the rural groundwater workshops, moderated a session focused on the hydrology of the Coconino Plateau.

Abe Springer started the session off. Springer is a professor and well-recognized water expert at Northern Arizona University who has been working across the Coconino Plateau for more than three decades.

Springer presented an in-depth overview of regional hydrogeology, stressing some of the unique facets of Northern Arizona’s groundwater situation. The Coconino Plateau is made up of a complex mix of layered volcanic and sedimentary formations, including karst, which means water often moves through faults and fractures that can be difficult to access and manage.

In contrast to other parts of Arizona, groundwater recharge here depends largely on precipitation, and particularly late-season snowmelt. Springer emphasized that groundwater in the area is not ancient and instead originates from precipitation in recent seasons.

Springer's research also indicates that unlike other parts of the state, climate change and changes in the timing and duration of the snowpack, not overpumping, are the dominant factors driving groundwater levels in this region.

Arizona’s groundwater policy and management

Haley Paul, Arizona policy director for Audubon Southwest, drew further attention to the importance of better data on area aquifers.

“We need a baseline understanding of what’s going on in our aquifers. More data helps refine the kinds of models we can use to inform our decisions,” said Paul. “Even though we’re not in a crisis, there’s still the risk of someone drilling a deep well without an impact analysis — so having baseline protections is critical.”

Paul also noted that Tribal settlement agreements play a major role in groundwater management by resolving longstanding claims and establishing protection zones, which benefits all water users by providing certainty and avoiding further protracted litigation.

Addressing regional groundwater needs and opportunities for economic development

Kristen Keener Busby of the Babbitt Center for Land and Water Policy—a key partner in these rural groundwater workshops—moderated a panel featuring Jess McNeely, planning manager for Coconino County, Mayor Clarinda Vail of Tusayan and Gail Jackson of the Economic Collaborative of Northern Arizona. The panel explored how land use and economic development plans can align with long-term water availability in the region.

McNeely noted that while Coconino County is the second-largest in the country by area, its authority over water is limited due to the prevalence of federal land ownership. The county comprehensive plan supports conservation and smart growth, but tools to assess water adequacy remain limited.

Mayor Vail described Tusayan’s reliance on deep wells and seasonal tourism demand. Despite reclaimed water systems that cut potable use in half, the town lacks control over its privately managed water service. Vail stressed the need for enforceable groundwater protections in rural areas.

Jackson focused on attracting low-water, high-wage industries and suggested evaluating proposals by "jobs per gallon" to align with regional identity and values. “Does it fit our community? Is it good for the region?”

All three underlined that successful groundwater planning in Northern Arizona depends on strong collaboration, informed decision-making and the ability to align development with long-term water availability.

Status of the Northeastern Arizona Indian Water Rights Settlement Agreement

The landmark Northeastern Arizona Indian Water Rights Settlement Agreement (NAIWRSA), still awaiting Congressional approval, is the largest Indian water rights settlement in U.S. history. It is aimed at securing over $5 billion and major water allocations for the Navajo, Hopi and San Juan Southern Paiute Tribes.

Cora Tso of the Kyl Center for Water Policy, a pillar of the Arizona Water Innovation Initiative, provided legal context, emphasizing that Tribal water rights stem from federal Indian law, which guarantees water sufficient to sustain Tribal homelands.

“Water management in Northern Arizona has been very siloed,” Tso said. “It took 40 years for this settlement to come to fruition. It’s a negotiated compromise and people have had to give up important claims to get to this point.”

Tso also stressed the importance of respecting Tribal sovereignty.

“Northern Arizona is home to nine separate sovereign nations, each with their own water management practices and historic and present uses. These governing bodies are in addition to the cities, the state and the federal government, but are often not holistically included in future planning discussions,” says Tso. “We cannot dilute the sovereignty that Tribal nations have when it comes to the region’s management of groundwater and water resources.”

Crystal Tulley-Cordova, the principal hydrologist with Navajo Nation Department of Water Resources, described the deep cultural and spiritual significance of water and outlined major disparities: one in three Navajo lack access to clean water, and Arizona lags on infrastructure investments. She highlighted threats from legacy uranium mining, brackish water and groundwater overuse.

Infrastructure projects aim to close these gaps, and Navajo-led monitoring is advancing sustainable planning.

Tso stressed that ultimately, NAIWRSA seeks to balance Tribal sovereignty and regional cooperation, offering a legal and practical model for future water rights resolutions across the western US.

Community collaboration

The workshop drew a diverse set of local leaders and community members, highlighting the value of cross-sector and intergovernmental collaboration, from mayors to researchers to Tribal representatives.

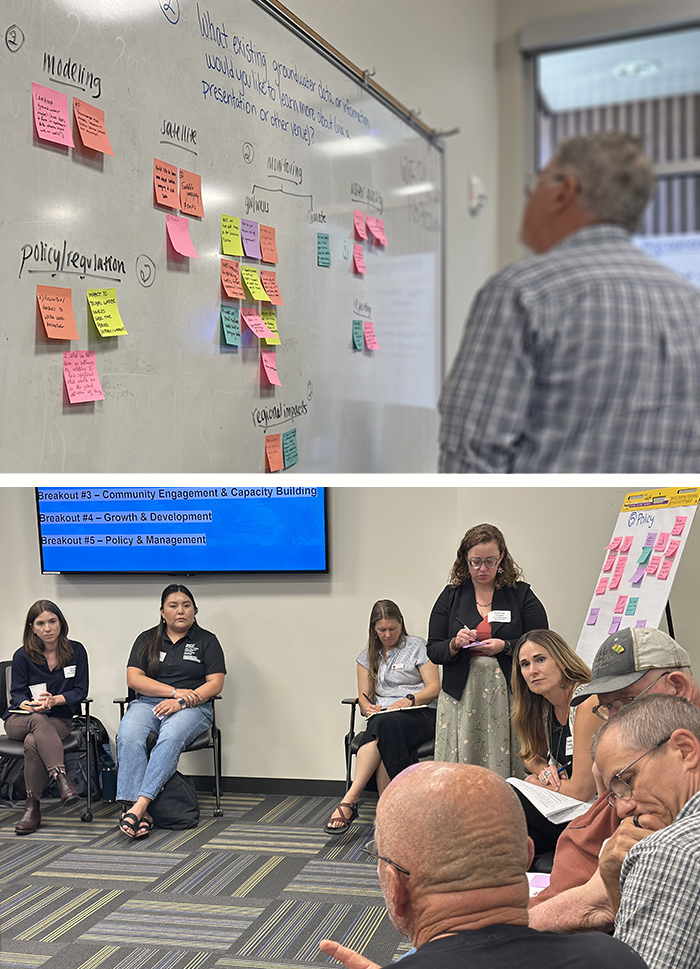

During the workshop, participants split into breakout groups to focus on recharge, data, engagement and policy. One group stressed identifying suitable recharge areas based on water quality and legal clarity. Another focused on improving data collection before a crisis emerges.

A third group discussed the need for culturally relevant communication, especially with Tribal communities. The final group called for better policy understanding, improved well data and stronger infrastructure to support water movement.

Pete Furman, Sedona council member and vice chair of the Coconino Plateau Watershed Partnership, joined the workshop to better understand groundwater dynamics in Northern Arizona.

“The workshop brought together smart, engaged people and challenged our assumptions,” Furman said. “It reinforced Sedona’s need to be a proactive regional partner.”

Erin Young, water resources manager for the City of Flagstaff, found the workshop valuable for its rare opportunity to gather diverse voices, particularly around housing, water planning and Tribal perspectives.

“We talk about water a lot in Northern Arizona, but this workshop brought everyone together in a way that doesn’t usually happen,” said Young.

Blake Anderson of Mogollon Water Management raised concerns about over-extraction in southern Navajo County and the need for more data and regulation.

“I support small water utilities,” said Anderson. “This was a great space for knowledge sharing. Going forward, partnerships and monitoring are key.”

Michael Macauley, a rancher in Northern Arizona, highlighted the challenges of accessing deep groundwater and the high electricity costs of pumping. He says most local ranches, including his own, rely on impoundments to capture rain and floodwaters.

“From my standpoint, it's very useful to bring people together,” says Macauley. “I think the most progress was made in the breakout sessions because we were able to get into specific topics and try to understand the different perceptions we all have.”

Michellsey Benally, water advocacy manager for the Grand Canyon Trust, was instrumental in bringing members of the Navajo Nation to the workshop. She highlighted the importance of long-term relationship-building and accessible, culturally relevant information.

“This workshop is a great tool for rural communities to define their own water priorities,” said Benally. “The strength of this approach is that communities decide how to use what they learn.”

Post-workshop evaluations show that participants left more informed and confident in their ability to collaborate on groundwater issues.

Looking forward

Moving forward, Doba is particularly interested in continuing to pursue more data and information that can be used for the basis of decision making, as well as pursuing identification of improved criteria that can be used for a determination of an adequate water supply designation for the Coconino Plateau from the Arizona Department of Water Resources.

"We don’t have a big problem now, and that’s the point. You hate to act after it’s already a crisis," said Doba. "We’re trying to be proactive, to protect groundwater before we ever get there."

Northern Arizona’s communities are aligning data, development and groundwater planning to be proactive. Local leadership shows that even in the absence of statewide mandates, rural regions are stepping up.

“We are now working with communities in three vastly different parts of Arizona, ranging from Cochise to La Paz counties and now here on the Coconino Plateau,” said Michelle Oldfield, community engagement specialist with Impact Water - Arizona. “Hearing from residents, it is clear how unique these areas are.”

Workshop participants were clear that in Northern Arizona, the future depends on uncovering, understanding and protecting what lies beneath, and doing it together.

“We are working toward a next generation groundwater management approach in Arizona,” said Dave White, who leads the Arizona Water Innovation Initiative. “There are multiple pathways to protect Arizona’s rural groundwater, and we are dedicated to working with communities to share the best available science and support their efforts to develop local solutions.”

Related stories:

- Momentum to address Arizona’s rural groundwater issues

- An Arizona community comes together to bolster rural groundwater resilience

- Community partner profile: La Paz County resident DeVona Saiter discusses rural groundwater issues

- Empowering rural communities with trustworthy groundwater information

- Arizona’s Tribal water rights settlements status

- Supporting rural communities to protect their groundwater

- Navigating uncertainty: Collaborative solutions for sustainable water management in the rural west