Coaxing water from air could stretch resources, ASU researcher says

One number buzzed among the crowd gathered at a recent conference in Tempe: 1 billion cubic meters of water per year. That’s how much water Paul Westerhoff suggests we should aim to pull from the sky.

At the third International Atmospheric Water Harvesting Summit held Jan. 15-16 at Arizona State University, Westerhoff and others discussed a promising alternative supply of water for the world’s water woes: the air. How long might it take for atmospheric water harvesters to innovate their way to reaping a billion cubic meters per year?

“Less than 10 years,” Westerhoff said. “This is not drying out the world by collecting it.”

Western governors called to Washington

ASU and SRP use cutting-edge airborne technology to measure the state’s snowpack

“Mapping snow cover with these airborne technologies is a first of its kind for the state of Arizona,” said Vivoni, also with the Arizona Water Innovation Initiative in the Julie Ann Wrigley Global Futures Laboratory. “We are excited about using snow maps in forested regions of the Salt River to improve runoff forecasts and train algorithms that apply artificial intelligence.”

NASA Snow Planes Help ASU, SRP Hunt for Precious Phoenix Water

"These machine learning and AI techniques allow unprecedented views of the Earth’s land surface," Vivoni told ASU’s Arizona Water Innovation Initiative, which has been building the algorithms and visual tools that local water managers will rely on.

ASU, SRP project takes flight to improve water supply forecasting

The data collected during the flights will be analyzed and used to test hydrologic forecasting models developed by ASU Professor Enrique Vivoni with the School of Sustainable Engineering and the Built Environment. Vivoni is the primary investigator for the joint project.

“Mapping snow cover with these airborne technologies is a first of its kind for the state of Arizona,” said Vivoni, also with the Arizona Water Innovation Initiative in the Julie Ann Wrigley Global Futures Laboratory. “We are excited about using snow maps in forested regions of the Salt River to improve runoff forecasts and train algorithms that apply artificial intelligence.”

ASU and SRP snowpack study begins

This advanced technology will be used for the first time in Arizona. On January 21, the first flight will depart Safford for a 5-6 hour flight over northeastern Arizona. Depending on the weather, the two remaining flights will be scheduled over the next two months.

Enrique Vivoni, a Fulton Professor of Hydrosystems Engineering at ASU, joined “Arizona Horizon” to discuss how this study will impact the Phoenix water supply.

'Water bankruptcy': U.N. scientists say much of the world is irreversibly depleting water

Jay Famiglietti, a hydrologist and professor at Arizona State University, said embracing the term "water bankruptcy" is "a brilliant way to convey that the water resources have been mismanaged, excessively utilized, and are no longer available for current and future generations.”

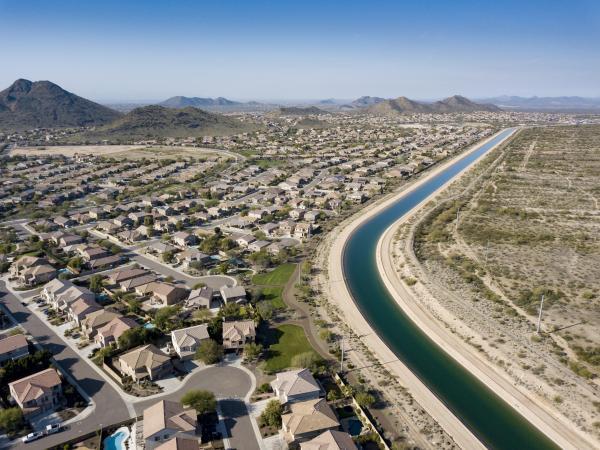

U.S. Bureau of Reclamation weighs Colorado River drought plans

“What we’re talking about is the rules for operating the Colorado River system,” Sarah Porter, Director of the Kyl Center for Water Policy, said. “Any change in how that system is operating requires review under NEPA (National Environmental Policy Act). What the feds released was a very thorough analysis of how a series of different options would work.”

Rep. Crane Introduces Bill To Codify Yavapai-Apache Nation Water Rights Settlement

A central component of the settlement is the Cragin-Verde Pipeline, a roughly 60-mile-long pipeline that will deliver surface water from the C.C. Cragin Reservoir on the Mogollon Rim to the Verde Valley. The pipeline will provide reliable drinking water to the Nation, reduce groundwater pumping, support housing and economic development on the reservation, and contribute to the sustained health of the Verde River, as explained by the ASU Arizona Water Innovation Initiative.

New aerial technology aims to predict water management in Phoenix area

"Students at ASU and researchers there— they’re going to take the outputs of the snow mapping that the aircraft is doing, to improve the predictions of the amount of water coming into the reservoir," said Professor Enrique Vivoni of the ASU School of Sustainable Engineering and the Built Environment. "So that we know ahead of time, weeks ahead, what's the water supply in the Valley we have for use later on this year."