Matching groundwater withdrawal and recharge locations in the Valley of the Sun

The Phoenix metropolitan area hides a valuable source of water underground – a large and ancient aquifer. As is true for many arid areas around the world, this groundwater provides tremendous benefits, including stability in times when surface water supplies are reduced.

While generally well managed under Arizona’s 1980 Groundwater Management Act, decades on, the aquifer is facing new challenges.

The Kyl Center for Water Policy at ASU’s Morrison Institute recently released a report examining groundwater sustainability in the greater Phoenix area. The Kyl Center is one of the pillars of the Arizona Water Innovation Initiative (AWII), a multi-year partnership with the state led by Arizona State University’s Julie Ann Wrigley Global Futures Laboratory in collaboration with the Ira A. Fulton Schools of Engineering.

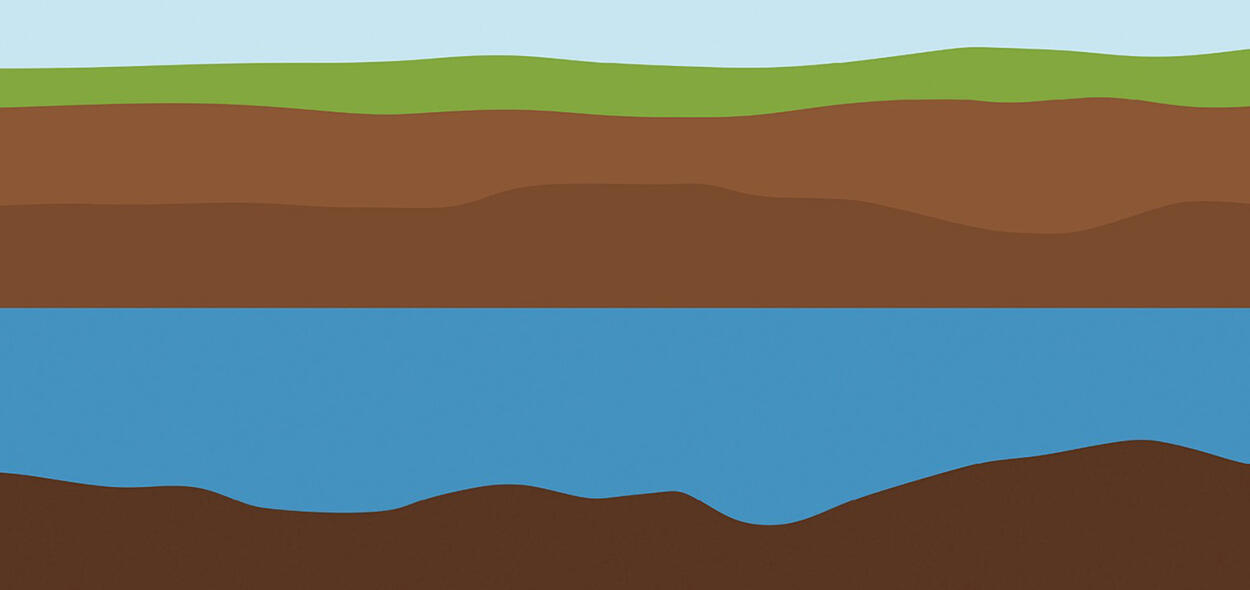

“We have a solid groundwater management framework and are doing well when it comes to the amount of water withdrawn and recharged,” says Kathryn Sorensen, director of research at the Kyl Center and lead author of the report, “but there is a mismatch between where we are withdrawing groundwater and where we are putting it back through recharge and replenishment. This can lead to areas of aquifer compaction and land subsidence, permanently reducing the ability to recharge groundwater in the future.”

The report explains that the discrepancy between groundwater withdrawal and recharge locations can largely be attributed to workarounds with the state’s Assured Water Supply program that allow entities to pump groundwater in one area of the aquifer and recharge it in another. The locations might be nearly one hundred miles apart.

“The Assured Water Supply rules, created as a result of the 1980 Groundwater Management Act, were extraordinarily controversial because they entailed enormous investment in renewable water supplies,” says Sorensen. “There was a lot of pushback, mostly from developers, but also from some cities really struggling with the expense, and so a couple of workarounds were developed.”

For example, developers, cities, private water companies and others are allowed to pump groundwater if they can demonstrate there is one hundred years of groundwater physically available below their community. They are obligated to recharge that water afterward, but there is no requirement that recharge take place near where the groundwater was pumped.

“In some ways that approach makes sense,” says Sorensen, an economist who also spent many years as a practitioner with the City of Mesa and then the City of Phoenix directing their water and wastewater utilities. “It is much less expensive to rely on groundwater wells and recharge than it is to build a surface water treatment plant.”

“Wells can be drilled right next to where you need the water, which also minimizes the need for transmission mains and other expensive infrastructure,” she continues. “If you're pumping in the same area you are recharging, it is not necessarily a problem, but that is not what we are doing.”

The solution, Sorensen explains, is to uphold and improve the investments that the state has already made in groundwater management. That has been challenging because passing the Groundwater Management Act alone was a huge accomplishment. While the Act has been adjusted over the years, the changes that remain to be made will likely be much harder and more expensive to achieve.

“There are trade-offs between short-term economic gains and long-term regional stability,” says Sorensen, “and those trade-offs make it politically difficult to enhance groundwater management.”

The shortage declaration on the Colorado River means that protecting Phoenix’s groundwater resources is even more important. Central Arizona has long relied on water from the river to recharge its aquifer, but with supplies cut by roughly half, sustainable groundwater management is even more critical.

The report puts forth several more specific recommendations to improve groundwater sustainability in the Phoenix area, including requiring recharge to occur within the same area as pumping, increasing groundwater withdrawal fees and discontinuing new groundwater pumping permits.

“We need to up our game when it comes to protecting our groundwater,” says Sorensen. “The cost of delaying investments in the infrastructure that can address groundwater decline is the irreparable loss of aquifer capacity. That becomes a disadvantage to future generations. Even for solely economic reasons, it's imperative that our groundwater supplies are secure.”

Groundwater sustainability is an issue not just in the metro Phoenix area, but across the state.

“The work that Jay Famiglietti and other researchers with AWII are involved in is extremely helpful in identifying areas of groundwater overdraft and quantifying the impacts of excessive pumping,” said Sarah Porter, director of the Kyl Center for Water Policy. “We are putting forward an ‘all hands on deck’ approach, and that’s exactly what the state needs right now.”