Hot droughts and summer floods are all in a day's work for the Arizona State Climatologist

Helping her parents set sandbags out around her childhood home to protect it from a flood is one of Erinanne Saffell’s core memories from growing up in the Phoenix metro area. That event sparked an interest in weather and the climate that continues to this day in her role as the Arizona State Climatologist.

“Most meteorologists and climatologists have something from their formative years that sets them on this path,” says Saffell. “For me it was water. Because we’re in Arizona, it was a question of having both too much and too little water. I was fascinated.”

Saffell’s formal training is as a geographer, and all three of her degrees come from ASU, which is also where she now heads up the Arizona State Climate Office.

“As a state climatologist, you have to be trained in meteorology and things like statistics. But understanding patterns is critical, and geographers are all about finding those patterns,” says Saffell. “If it rains along the Mogollon Rim, is that water going to run down and hit Payson? Are there people in Payson at risk from a flooding event? Those are the kinds of things I think about as a geographer.”

State climatologists play a unique role across the US, focusing on the needs of their particular states. In Arizona and the southwestern states, Saffell says that tends to mean concentrating on water supply, droughts and wildfires, as well as heat. All of these phenomena are of course related.

“For example, if we look at temperatures since the early 1900s, the state has increased by about two and a half degrees. Those hotter temperatures make for a thirstier atmosphere, meaning the atmosphere takes moisture from the ground and plants through evaporation,” says Saffell. “We consider that a water loss. Paying attention to those hotter temperatures helps us understand what's happening with our water supply.”

State climatology offices were established in 1973 and led at the time by the National Weather Service, but later handed over to the states. Every state administers their climatology office differently, and here in Arizona the position is supported by ASU. Saffell is currently serving as the sixth Arizona state climatologist.

“I wear a lot of hats and get to serve the people of my state in different ways. For example, we've measured the urban heat island in Sedona. We go talk with K-12 students and with the media to help them understand what's going on with Arizona's climate.”

The suite of information that Saffell ably shares takes the skills and knowledge from a long career spent analyzing weather and climate patterns in Arizona. She has to understand everything from the atmosphere to water to soils. She also has to be able to communicate what she is finding effectively.

“Ultimately what I do is provide context. People ask, are we seeing bigger changes, smaller changes? What are the trends? Being able to provide that context is essential,” says Saffell. “These things are more than just numbers.”

During the summer, one number that people tend to pay attention to is temperature.

“In July 2023, Phoenix became the hottest monthly US city. Fortunately in 2024, we turned over that record to Needles, CA. Still, this summer was the second hottest July for most Arizona cities and the second hottest July statewide.”

Heat is, of course, an issue of increasing concern in Arizona. But some aspects of increasing temperatures are more concerning than others.

“Daytime temperatures are increasing, but the nighttime temperatures are increasing at a greater rate and that is a huge issue. Those nighttime temperatures are being exacerbated by urbanization, not just in metro Phoenix, but across the state,” says Saffell. “But we do understand a lot about what's going on with the urban heat island and have made advances to help mitigate these higher temperatures by, for example, finding ways for it to go back into the atmosphere versus keeping it stored in buildings.”

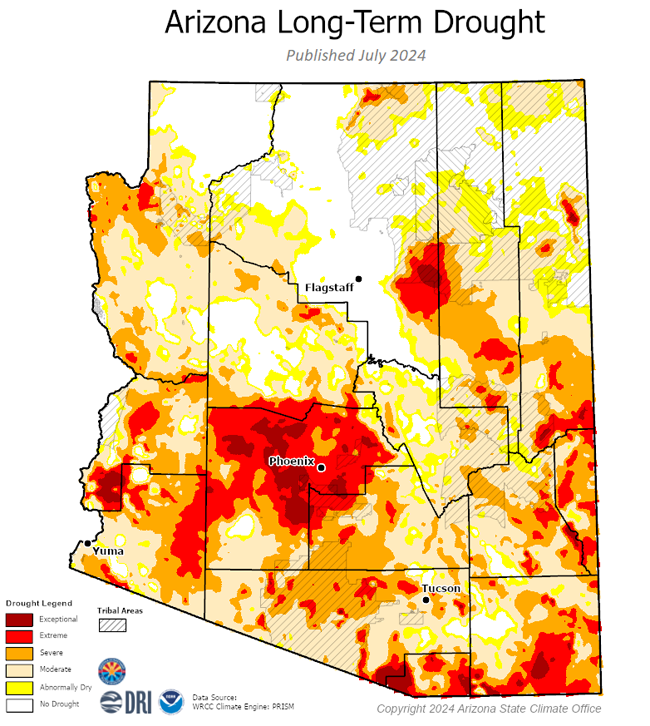

Long-term drought is another particular concern for Saffell. She serves as the co-chair of the Arizona Drought Monitoring Technical Committee. The committee evaluates both short-term and long-term drought in the state and makes reports to the governor every six months.

“One of the first things to understand about Arizona is that we have an arid and semiarid climate, so we're susceptible to drought conditions,” says Saffell. “But what we've been dealing with for the last 30 years is a consistent lack of precipitation.”

Precipitation is measured in what is known as the water year, which runs October 1 through September 20. Arizona receives 12 inches, on average, of precipitation per water year.

“Over the last 30 years, it's not that every year has been dry, but 20 of those years have been below average. If you have two or three dry years and one wet year, it’s not enough to make up that precipitation deficit,” says Saffell. “This kind of chronic, long-term drought has different impacts than short-term droughts. When you’re down one inch during drought, it makes a huge difference here and we have to manage water effectively.”

Heat and precipitation become visceral issues for Arizonans during the monsoon season. Without cooling rains, temperatures can remain high for extended periods. Saffell says that while the monsoon season in Arizona is highly variable, there hasn’t necessarily been a change in the amount of precipitation falling during the monsoon.

“It is hot this year. It was hot last year. Last year was also very, very dry. This year, we're at about average for precipitation,” says Saffell. “However, some places may be drier than others. For example, last year some of the western counties – Yuma, La Paz, Mohave – were really wet. This year, the west has been pretty dry so far, and we're seeing a lot of rain in the southeast and along the Mogollon Rim.”

More than anything, heat, drought and seasonal storms are issues that Saffell wants people to understand and feel that they can address.

“Arizona is beautiful. I love my state. But it can also be deadly. I want folks to understand how the weather and climate operate so they can stay safe,” says Saffell. “For example, the monsoon seasons bring really dramatic weather, including hail and wind storms. But understanding how the monsoon operates keeps everyone safe.”

To that end, Saffell maintains a website with curated information useful to Arizona residents. She is also active on social media, alongside a larger community of weather enthusiasts and storm chasers posting to #AZwx. In addition, she hosts monthly webinars delivering that information in digestible pieces.

“I put together drought, water and climate information and provide context for the past, present and future,” says Saffell. “We have all our reports online so you can delve pretty deeply into what's going on with the state. And of course, I’m always happy to talk with folks.”