Asking why water tastes like water

Christy Spackman studies the tastes and smells in water. Her recent book, “The Taste of Water,” examines how scientific and technological innovation have changed the taste of bottled and municipal water.

Spackman holds a joint appointment in the School for the Future of Innovation in Society and the Arts, Media and Engineering Department at Arizona State University. Here, she discusses her book with Faith Kearns, director of research communication with the Arizona Water Innovation Initiative in the Julie Ann Wrigley Global Futures Laboratory at ASU.

Faith Kearns (FK): Tell us a little bit about your new book, “The Taste of Water.”

Christy Spackman (CS): The book explores how it is that water became municipal water. I also address how bottled waters came to be something we take for granted and assume should have minimal markers of the place it came from.

The book came into being in part because about 15 years ago I was walking in New York City and passed a pop-up shop for Vitamin Water. They had this spectacular display and people doing activities to demonstrate how you burn 10 calories as part of promoting Vitamin Water 10. I got interested in the way that our sensory perceptions of beverages shapes what we think they will do for our health. I did some preliminary research on mineral waters, and learned they were – at least historically – a functional beverage perceived to shape bodies, just like the Vitamin Water of today.

Water used to have incredible variety. For example, late 19th century and early 20th century waters had very different aesthetic profiles. I came across stories like one from St. Louis where water coming out of the tap was reddish colored, and people would have to let sediment settle out before they could drink it. Or folks in Chicago turning on the tap and having chicken feathers come out.

We can still experience some variety when we travel. My in-laws live in Jacksonville, Florida, and the water there has a much higher, naturally-occurring sulfur content than the water in Phoenix. It's a little hard for me to drink when I first get there, but I get used to it, especially if it’s cold. Nonetheless, I imagine a hundred years ago the difference between water in Jacksonville and Phoenix – with our nice, very salty, sometimes musty, earthy flavors – were really, really different.

FK: Taste seems hard to define because it is subjective. How did you approach this project given the challenges?

CS: It's helpful to know that my background is in food chemistry and sensory science. One of the things sensory scientists spend a lot of time doing is figuring out how you can take something as subjective as taste and make it more objective.

Sensory scientists have worked in the wine world, the food world and, more recently, in the water world to develop tools that allow them to talk about the subjective experience of taste. We can now describe sensory experiences across distance with a shared language, and increasingly tie that to a molecular experience. That allows us to then ask what the chemical cause of this sensation or that perceptual experience is. Do we want to boost it or tamp it down?

When wine producers are trying to describe the places their product comes from, they often mobilize this idea of terroir, which scholar Amy Beck has defined as the taste of place for wine producers.

When it comes to water, municipal water producers haven’t really wanted to highlight that taste of place. That's because of something I refer to as industrial terroir, which is the taste of place as shaped by human industrial activity. For example, you have the taste of a place related to rocks and minerals and such. Then there are additional things, maybe we're dumping animal carcasses into the water or have agricultural runoff, and they shift the flavor profile.

I’d add that terroir isn't just the taste of place, it's also the taste of the labor and care that goes into making something. To me, then, industrial terroir carries with it the work that engineers and scientists and technologists have done to make it so we don't perceive those smelly, tasty molecules that would be present in our water otherwise, while they're also making the water safe for us.

FK: Would it be helpful to work with people to appreciate the terroir of water?

CS: In my ideal world, I'd move beyond liking and disliking to just say, wow, I'm so excited that this earthiness is coming through the Phoenix water supply in October and November. I can recognize what it's telling me – that the weather has changed and the flora in the water are growing and happy because they're not so hot. At the same time, in reality, I don't necessarily love it.

However, it’s pretty cool to taste water and recognize the ways it links me to the environment. Sometimes I even think the waters where we live include necessary minerals for our bodies. Consider how much you need to replace your electrolytes here in Phoenix, and we happen to get salty water. I'm not certain at what point we develop a form of connoisseurship and appreciation for those flavors.

FK: You take a creative approach to sensory experiences in your work, like with AWTr Pops. Can you talk a little bit about that project?

CS: In many ways my creative approach comes from trying to teach students in an embodied fashion. In other ways it comes from critiques I have of the food industry. I should say I love the industrial food industry. They do some cool things and some problematic things, like sticking a lot of foods in packages that are filling up our landfills. These critiques open up an intriguing possibility about what food science could be.

The AWTr Pops project is an example of an attempt to reclaim food science. AWTr stands for Advanced Water Treatment, which is another term for water recycling, direct potable reuse or advanced water purification. As a kid I liked Otter Pops, and I thought it would be fun to play around with.

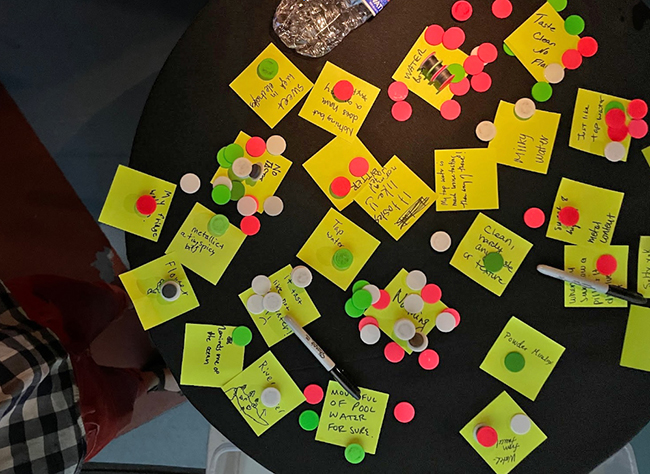

My colleague Marissa Manheim and I had been doing research with folks we call ‘tap water hesitant consumers.’ These are people who opt out of using their tap water and use bottled water. We had worked with them to develop an exhibit around what we anticipate a future with potable reuse might look like.

A year later we brought them back together because the state was really moving forward with water treatment technologies. We told them we'd love for them to tell us a story using flavor about what you think the future with these kinds of water treatments might be like.

Then we partnered with Paletas Betty, a local gourmet popsicle company. They developed six different paletas that are essentially an edible version of each of these people's stories. When you eat an AWTr Pop, you are viscerally engaging with the future they think might happen.

FK: Are there lessons here for water managers and consumers?

CS: I hope anyone who reads the book will take away a deep appreciation for the amount of work that goes into this everyday food we tend to not think of as a food, we instead think of as a utility. The fact that our tap water tastes as good as it does and is generally as safe as it is, is amazing.

I also hope people take away an appreciation that when they perceive something in their water, they're often tasting place and, in some cases, tasting time. You're engaging with processes that have been going on for centuries and millennia.

I hope water managers will allow their conversations with consumers around taste and smell to be catalysts for improving community collaboration. I also hope they can consider saying things like, 'yes, there are taste and odor issues and these are qualities that are unique to our region, and we recognize that you may not love them initially, but it's okay that they're there.'

When I talk with water managers about recycled water, it’s clear how much water is being wasted because consumers think water should taste of nothing, and so they buy a whole house filter. I recognize my hard water is also messing with my appliances, but those whole house filters use a lot more water than is necessary just so people have something delivered they perceive as being better tasting. It's an exciting opportunity to reconsider why we operate according to those tastes.

Finally, I would invite people to organize a water tasting with friends, and in the book's conclusion I offer a pretty basic guide for how to do one. It’s valuable to think about what you perceive in the water and what that tells you instead of whether you like it or not.

Register to join Christy Spackman for a book and beer event at Changing Hands Bookstore on Friday, March 22, 2024 at 5pm MT.